The Great Stagnation

How Technological Stagnation May Be Ending

Iman Olya

23rd August 2021

Part 1: Pigeon Fodder

Part 2: Genius and God

Part 3: Granny Really Lived

Part 4: Glass Half Full

Part 5: Collision Course

Part 1: Pigeon Fodder

She unlocked the door of room 3327. A sudden waft of stale bread hit her. She pulled in her trolley, frantically searching for some perfume to lighten the load on her nostrils. Working in the New Yorker hotel, she was used to all smells and sounds. But something was off. She couldn’t hear the pigeons. In fact, the pigeon feed was scattered everywhere.

She grabbed her dustpan and brush and began sweeping. She called his name expecting to wake him up as usual. No answer.

“Sir, the pigeons of New York need their food! Let’s get you to Bryant Park!” Still no response.

Done sweeping, she emptied the fodder in her bin and started scanning. The bedroom door was open and as she walked over, she recognised his fragile slumped body in the sheets. But he was still. The greatest inventor of the modern era had departed.

On January 7th 1943, this esteemed inventor passed away at the age of 86. He had spent 10 years living in the New Yorker hotel at the grace of his old friend and patron, George Westinghouse. He survived on a diet of crackers and milk and cut a gaunt figure when entertaining noble guests like King Peter II of Yugoslavia and Serbian sports stars.

But he was done with this life. His parting words to his mother read:

“ All these years that I had spent in the service of mankind brought me nothing but insults and humiliation.”

This prodigious inventor lived in the last great era of innovation; a period of rapid technological advancement and productivity growth. He himself held almost 300 patents, even though he notoriously disregarded the commercial elements of his inventions. It is speculated that he would have had thousands more patents had he been more business savvy. He even gave up the equivalent of $300m in the pursuit of scientific growth.

But he was not appreciated in his time. In fact, he was smeared and marginalised by his contemporaries and fellow inventors. The great Thomas Edison had dedicated millions of dollars and significant influence to shun our great inventor to the dark hallways of the New Yorker room 3327. He had contributed so much, only for his last friends to be the rats of New York’s skyline. Only in feeding pigeons did he find peace and solace from this life.

It is fitting that as we now head into a new age of scientific discovery, his name is a shining light - a beacon - of the new tech movement. In large part we can thank Elon for this. But unfortunately for our esteemed, gaunt, tired inventor, it is a pity that he was not sent off with the necessary appreciation fitting of one of the greatest minds in history.

Part 2: Genius and God

Today Nikola Tesla is a giant. Not just by name - H/T Elon - but by his invention. His contribution to the design of today’s alternating current electricity system, alongside his hundreds of other practical designs, helped support the weight of the last century’s technological progress.

Tesla was by no means a messiah though. He accelerated the path towards electrification, but was not the sole proprietor of this. And at some level, it seems in death he has received such praise and adulation that he is made out to be God, while his contemporaries were the Devil.

It is true, he was a genius. But there were other incredible vessels of innovation during this time too. In fact, we probably cannot conceive how forward-thinking and steadfast the last era of rapid innovation was. And for good reason. Most of us have not actually experienced it.

Part 3: Granny Really Lived

“ The single most important economic development in recent times has been the broad stagnation of real wages and incomes since 1973, the year when oil prices quadrupled. To a first approximation, the progress in computers and the failure in energy appear to have roughly canceled each other out. Like Alice in the Red Queen’s race, we (and our computers) have been forced to run faster and faster to stay in the same place. ”

Peter Thiel

The Great Stagnation, coined by Tyler Cowen in his 2011 book, and bolstered by powerful voices such as Peter Thiel, posits that three major forces, or low-hanging fruit, have shaped innovation in the US in the c. 50 years prior to 1973:

the ease of cultivating free (legally, not morally) and unused land;

the rapid invention from 1880 to 1940 which capitalised on the scientific breakthroughs of the 18th and 19th centuries;

the large returns from sending intelligent but uneducated children to school and university.

Cowen also mentions two further juicy fruits in the form of:

4. cheap fossil fuels and;

5. the strength of the American constitution.

He presents multiple examples, including data to back this up. Cowen shows that there was rapid economic growth in the form of median family income after WW2. But post 1973, that rate of growth tapers off significantly. The supposed rapid improvements in technology that are meant to have improved our everyday lives, are not showing up in real income terms. In fact, the bottom 20% of earners have seen a decline in real income since 1979.

Total Factor Productivity Growth tells a similar story. This is a measure of total output from the amount of input used. And you would expect this to rise, as we would expect to produce more output from the same (or less) inputs as we become more efficient in our manufacturing processes.

However, from the end of WW2 until the early 1970s, TFP growth averaged c. 2% per year. From 1973 to the late 1990s it averaged just 0.5%. With the IT revolution in the early 2000s came another jump to 2%, but then since the dot com bubble we’ve seen only a 0.4% TFP growth.

Whatever method you use, two things are clear:

It’s clear that there has been a stagnation in economic growth in the last 50 years (although some make the argument that this is not true economic value as it cannot measure the impact of the internet in the short term - but we discuss this later).

It’s clear that 1973 was a turning point.

What is not so clear is why 1973 was the turning point. A number of theories are floated including:

OPEC raised the price of oil meaning fossil fuel-based innovation suddenly becomes far more expensive. And naturally stutters.

As the economy grows, the importance of healthcare and education develop rapidly. But this is hard to scale from a productivity perspective. As population goes up, there are more illnesses and a greater number of sick people (especially with downgrades in diet over the last century). It’s also hard to grow productivity when you’re educating the vast majority up to a high school diploma. The increase is incremental and at the margins.

The incremental leap in technology was not as large as the previous half-century. Cars did not really change, beyond better fuel efficiency and some cooler gadgets inside them. Jumping from horse to car was a far bigger innovative gallop.

Holistic change is harder to achieve when the fundamentals or basics of science are already “figured out”. It’s why people like Einstein are so revered and why zero-based principles are likely to drive us forward. See my last essay on this here. But grasping science at the margin - i.e. trying to instigate change in increasingly specialised fields - means we are only making progress at the margins.

However, it is Cowen and Thiel’s anecdotal approaches to this which are most powerful.

Notably, Cowen used his grandma as an example - who happened to live during a similar period to Tesla. Cowen explains that his grandmother saw extreme levels of innovation in the half century between her birth in 1904 and her 50th birthday - everything from household appliances, emergence of cars, flush toilets, commercial airline travel and TV. Granny was living life.

Since then the changes have been incremental and not as world-shattering. Thiel adds nuance here:

“ We’ve had quite a lot of growth in the world of bits - but not in the world of atoms. E.g. supersonic travel, space travel, new forms of energy, medicines and medical devices etc. ”

Peter Thiel

And he puts that down to regulation, or lack thereof in the world of bits. For example, the hoops required to iterate on something existing, like a new FDA approved drug, are numerous. Whereas creating dopamine-massaging, life-altering social media apps in the early 2010s would have had very little government intervention.

Part 4: Glass Half Full

Of course, not all believe in the Great Stagnation.

Rational Optimists sit firmly in the opposing camp to Thiel and Cowen. Their belief is that we are hard-wired as humans towards pessimism. They point to the fact that much of our consumption in the internet age is free. Or almost free.

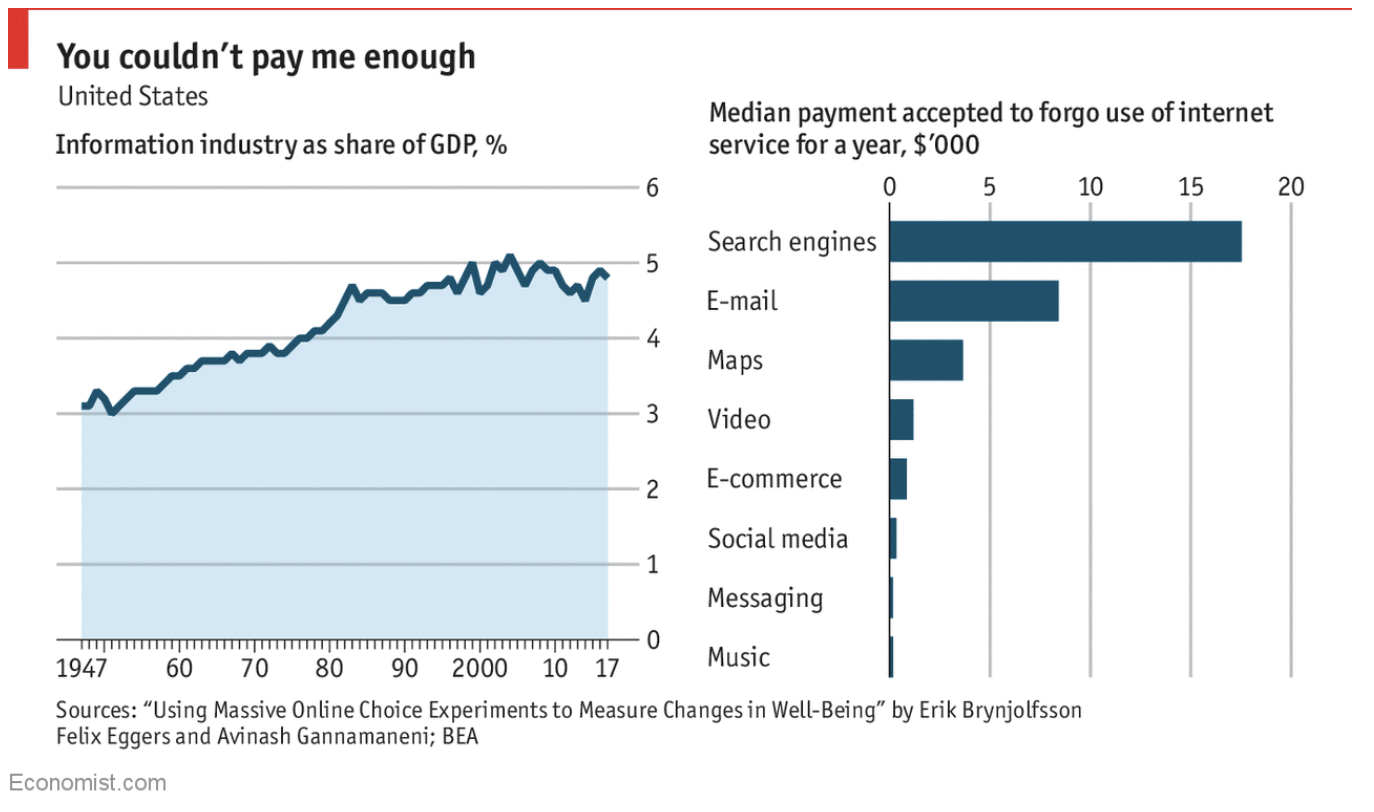

Internet giants like Google and Facebook do not charge for access. Zux’s value generation is therefore not included in national-income statistics. Another reason why GDP is flawed - it only accounts for stuff we part with our cash for. A study by three economists aimed to quantify this missed value - estimating up to $17,500 is the minimum median amount needed for us to stop using search engines for a year. So basically pay me 20 bags a year to live without Google (how would we live without immediately fact-checking our mates?! Also Consulting as an industry would likely die). Below are some more of these staggering numbers:

And it is obviously important to note, this is just the US. “Catch-up growth” as Alec Stapp mentions here, shows that bringing the rest of the world closer to the US’s privileged position should also not be overlooked. Just because the US is stagnating, does not mean the world is not progressing. We may have fallen into the trap of thinking the US is synonymous with innovation - which may have been true historically - but this is rapidly changing.

Regardless of what camp you sit in, there are reasons to be hopeful. Reasons to believe that a new age of Teslas, Edisons and iterations of the War of the Currents are on the horizon.

Part 5: Collision Course

In a recent interview with Lex, Tyler Cowen highlights how his thinking is evolving on this subject of stagnation (skip to 46:15). In his 2011 book, he saw the US emerging out of stagnation by 2030. He is now revising that target, seeing the rate of progress since the pandemic moving us into the next frontier.

Thiel agrees with this. He explains in the first 5 minutes of his interview with Cowen here how the intersection of atoms and bits will hopefully usher in a new age of innovation. One where our lives become upended and everyday human existence fundamentally shifts. Examples include driverless cars, biotechnology, MRNA vaccines, space manufacturing, wearables, nuclear fusion / geothermal energy, Starlink etc.

Seems like Tesla may be right when he said:

“ In the twenty-first century, the robot will take the place which slave labour occupied in ancient civilisation. ”

Nikola Tesla

But he also warned of the dangers of not doing enough. He explained that innovation was a non-negotiable right - something intrinsic to human growth. Without it we would be doomed. Famously he said:

“ I care not that they stole my idea. I care that they don't have any of their own. ”

Nikola Tesla

By being at the forefront of technological innovation for the next 50 years, this generation has the capacity and opportunity to forge the next Tesla. The new space race, the emergence of rapidly evolving AI capability and the intersection of bits and the body (e.g. Neuralink) offer new levels of optionality that we have not seen in decades.

We owe it to one of the greatest minds of the last century to pioneer in these areas and build on his legacy. Without it, our pigeons may forever remain unfed.

Subscribe to the rational letter

Every month over three thousand seasoned founders and investment professionals at VC firms, family offices, endowments, and sovereign wealth funds read the same email to better understand the tech industry.

Long-form essay with original ideas and thorough research, curated and emailed once a month. Nothing else.

Still not sure? See some of our long-form essays below.

Did you know we also have a leading podcast? Co-signed by the best in the industry.

Click below to return to the Home Page and see more.